Archive of Marcel De Baer

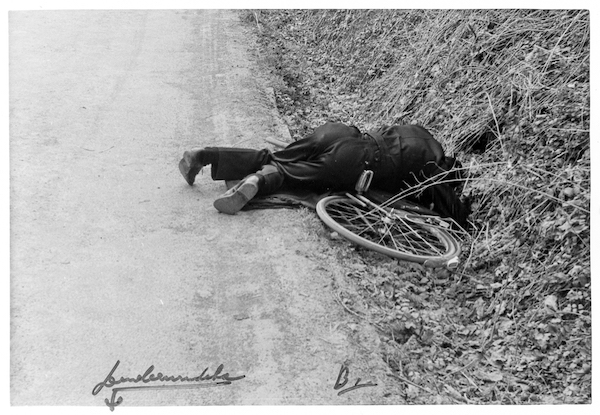

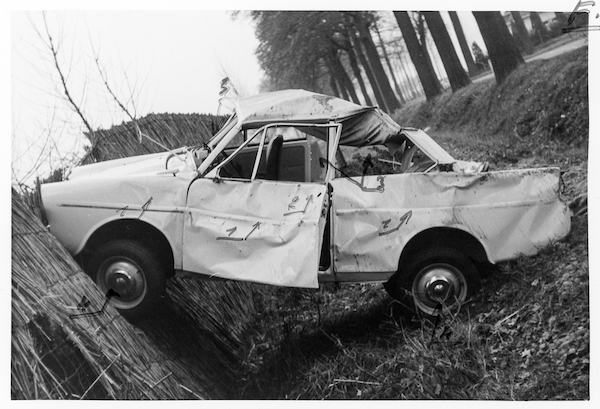

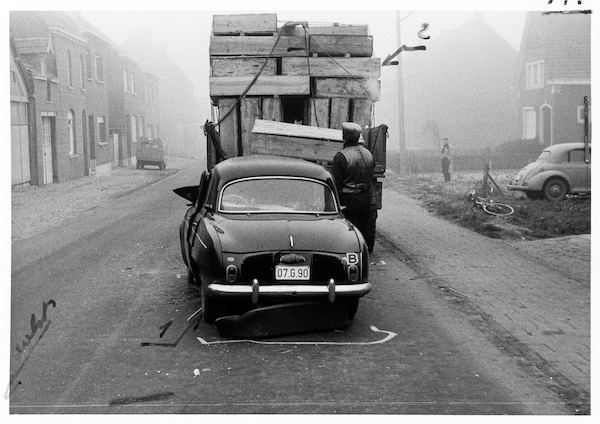

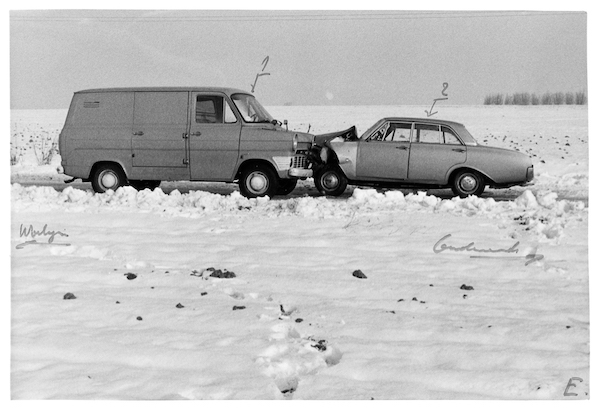

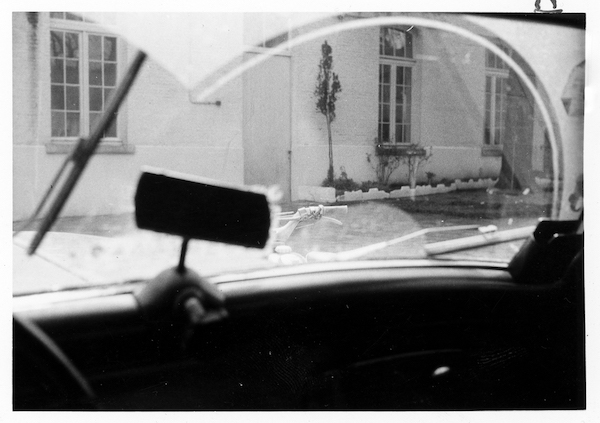

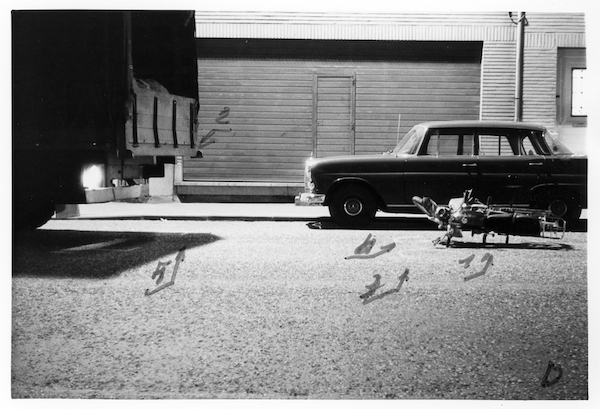

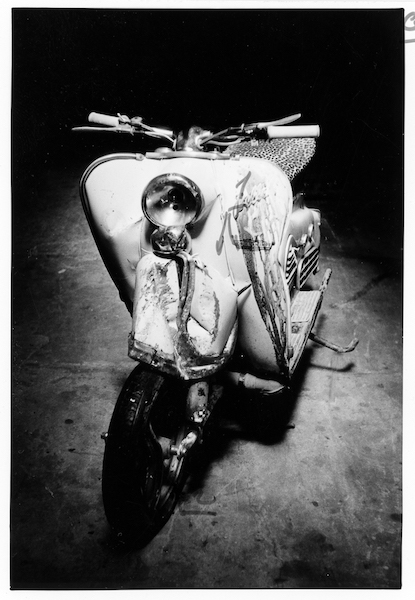

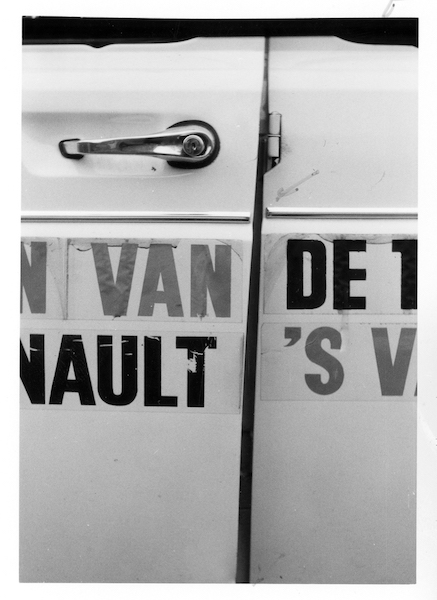

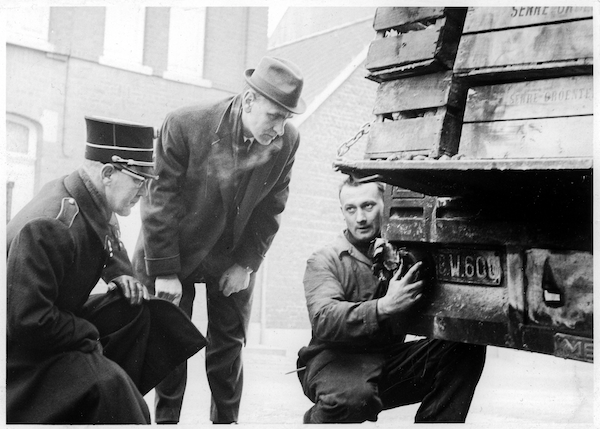

From 1961 to 1980, Marcel De Baer (Geraardsbergen, 1922-2014) was a collision expert for the public prosecutor’s office of the district of Oudenaarde, Belgium. In this capacity, he came at the scene of every major traffic accident that took place in the area to report on what had happened based on photos, measurements and technical drawings. Since De Baer kept a copy of every file intended for the court for his own archive, these were preserved until now. After De Baer’s death, a total of approximately 4,000 reports and ten thousand images – both prints and negatives – were found by his grandson Erik Bulckens in his grandparents’ attic. These pictures of a.o. skid marks, chalk lines, car wrecks, scratches, dents and even blood spatters, to which De Baer added arrows, numbers and annotations that correspond to descriptions in the original files, provide an insight into how he analyzed and reconstructed accidents. Since most crashes took place in the early hours, few people can be seen here. In these strangely stilled images, the metal seems to lie almost peacefully in the morning mist, contributing to the film noir atmosphere the photos radiate. Other images do show human presence in the form of groups of bystanders, or police officers who perform re-enactments of what happened in a somewhat surrealistic way. The latter provide, presumably unintentionally, some comic relief.

These images can be regarded as time documents – testifying a.o. to road safety in its infancy – but above all possess a remarkable beauty. This is not only due to the nostalgic atmosphere, the aesthetic of the old cars (often a Volkswagen Beetle), and the sculptural qualities of the car wrecks, but also to the contribution of the photographer. Although technically very well trained, De Baer had no artistic background nor ambition. For him, his photos were purely informative, taken for the purpose of research. However, these incentives seem at odds with his thoughtful lighting, framing, composition and attention to detail. He could have captured the damaged vehicles in a snapshot, but instead took the time to search for the perfect frame that also included seemingly unimportant information such as the surroundings or a crowd of onlookers. Was it De Baer’s formal control of the medium that unintentionally produced artistic images, or was there more to it? It is part of the mystery of this man who always performed his job conscientiously and dutifully and never left the house without his suit and hat on, even when he was called up in the middle of the night.

These atmospheric, poignant, melancholic and sometimes humoristic photos evoke associations with Weegee’s well-known crime pictures from the 1930s and 1940s (although these posses a much higher shock factor) or Andy Warhol’s 1962-63 ‘The Death and Disaster Series’ in which, by repeating press images of a.o. car accidents reflected on how the widespread publication of this kind of gruesome images renders readers immune to their impact. However, De Baer’s photos can best be compared to those of police photographer Arnold Odermatt (1925-2021) who photographed car accidents in the Swiss canton of Nidwalden between 1948 and 1993. Odermatt’s photographs possess the same skilful precision and also transcend the mere description of facts. Although Odermatt clearly acted more from an aesthetic point of view – in addition to the images he made for the police report, he also took additional, more carefully composed photos for his own use – his archive likewise raises the question whether a photograph can be regarded as artistic regardless of its initial, utilitarian intention.