100 | centennial

Saul Leiter - Jan Yoors - Louis Stettner

03/12/2022

28/01/2023

Gallery FIFTY ONE

Opening December 3rd 2022 from 2 – 9 pm

Gallery FIFTY ONE and FIFTY ONE TOO are proud to present ‘Centennial: Saul Leiter – Jan Yoors – Louis Stettner’: a group exhibition in honor of three of our artists who would have turned 100 in 2022 and 2023.

Read the full press release here.

View a full overview of the exhibited works here.

Saul Leiter – Jan Yoors – Louis Stettner

Instead of a comprehensive retrospective, this show is an eclectic homage with choices that highlight partial aspects of the inimitable oeuvre of all three artists. On view will be among others never-before-seen color photographs by Saul Leiter, next to a selection of his small-scale paintings. The lesser known collages from Louis Stettner’s ‘Héros du Métro’ series – atypical for his oeuvre – are shown alongside his beautifully captured portraits of the two Spanish fishermen Pepe and Tony. This exhibition will also be a rare opportunity to see and experience one of Jan Yoors’ monumental wall tapestries, in dialogue with his brightly colored gouaches and studies of the female figure in charcoal.

Jan Yoors (Antwerp, Belgium, 1922 – New York, US, 1977)

When talking about Jan Yoors, his fascinating life story cannot be ignored. Born as the son of Spanish glass artist Eugene Yoors and Flemish journalist and feminist Magda Peeters, Yoors grew up in a cultural and liberal environment. Fascinated by his father’s stories about the Spanish gypsies, Yoors first came into contact with a Lowara family – a tribe of Roma gypsies – at the age of 12 and decided to go travel with the Kumpania on and off for the next ten years. During World War II, he collaborated with the Allies to help the gypsies who were being systematically exterminated. He was captured twice by the German occupiers and was imprisoned until the end of the war under harsh living conditions. After his release, Yoors fled to the United Kingdom via Spain, eventually settling in New York in 1950, together with his wife Annebert van Wettum and their friend Marianne Citroen. Yoors would have two children with Annebert and one with Marianne, forming an unconventional household. Having led several lives in one, Yoors died very young, at the age of 55, from the consequences of a heart attack (weakened by his diabetes, which had already cost him both legs in 1974).

As a humanist and inspired by his experiences with the gypsies, Yoors harboured a lifelong fascination for other cultures and minority groups. After moving to New York, he began to explore his interest in the photographic medium, photographing not only the architecture of the city but also its various religious communities and cultural enclaves. In 1963 he made the documentary film ‘Only One New York’ (working title: ‘Tower of Babel’) about the city’s ethnic diversity. This exhibition includes a selection of vintage prints of the street photos Yoors took during the shooting of this film (which also appeared in a book of the same name, published in 1965).

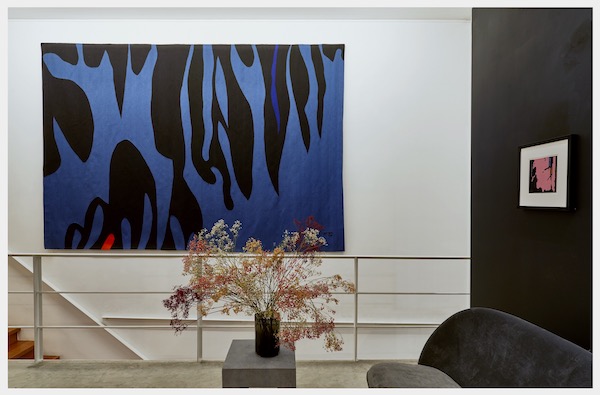

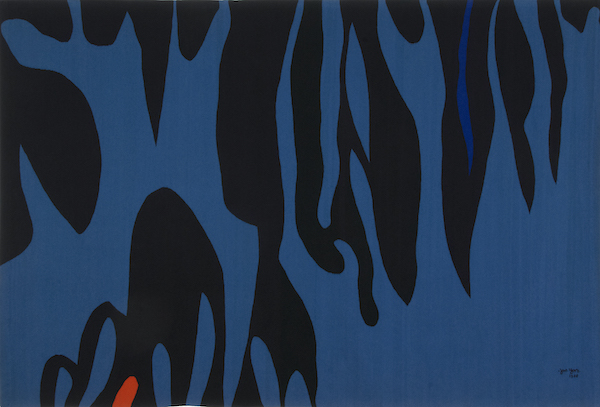

Besides photography, Yoors specialised in multiple media, which he simultaneously explored throughout his life, from gouache to drawing, sculpture and the most spectacular of all: tapestry. He became fascinated by weaving upon seeing an exhibition of medieval and Renaissance tapestries in London in 1946. Despite never having received much formal training, after his move to New York, he grew out to be a skilled tapestry artist, famous for the unique color palette of his creations. The role of Annebert and Marianne in this can hardly be overestimated; they collaborated closely with Yoors in the weaving of all of his designs, a painstaking job that could take 4 to 9 months to complete. While in the beginning Yoors’ tapestries were still largely figurative – narrative compositions of animals, biblical and mythical scenes – the tapestry ‘Jungle’ (1968) that can be admired in this exhibition is a typical example of the abstract, two-dimensional motifs in which Yoors began to excel at from the late 1950s. The flame-like shapes of this design create movement and, together with the vibrant color palette and impressive scale, lend the piece a sculptural sense of mass.

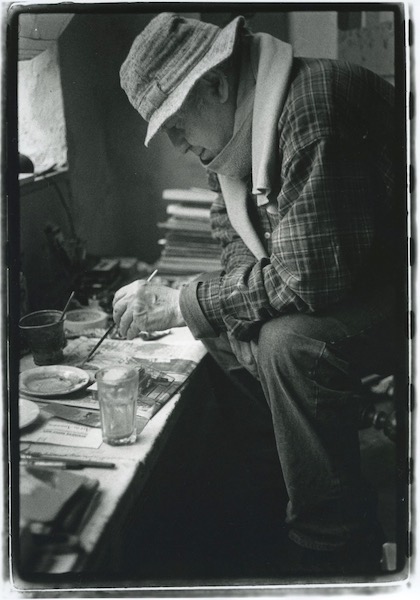

The use of bold colors and stylized forms as seen in ‘Jungle’ are a constant in Yoors’ oeuvre, regardless of the medium. interesting is the way in which these different media would sometimes interfere, such as the influence of Yoors’ photography and painting in the design process of his later tapestries. Starting from the late 1960s these were often inspired by shapes an graphic patterns Yoors found in his surroundings and photographed, such as layers of torn paper on a wall, dripping paint or broken glass, but also motifs he encountered in nature, like dunes, plant leaves and their shadows. These photographs of urban, geographic and natural origin were then cropped and enlarged to serve as the inspiration for the design of full-scale cartoons painted in gouache on the basis of which the tapestries were made. Towards the end of his life, when Yoors’ health deteriorated and his reduced mobility made him unable to paint on a large scale, the artist turned to create small gouaches of the kind shown in this exhibition. These paintings would likewise serve as a guideline for creating the tapestries, but, unlike their larger counterparts, were often preserved. Although they could be regarded as preparatory works, there is no doubt that these small-scale gouaches are nevertheless complete works of art in their own right.

Also characteristic for the later tapestries is the limitation of the color palette to no more than three colors, combined with heavy black lines. In the latter we see a resemblance with the thickly outlined charcoal drawings of female nude silhouettes on sepia-toned paper that are shown on the ground floor of this exhibition. Yoors started these linear studies – tight and closely cropped compositions in which the facial features are often kept out of sight – in 1948 and continued the series until the end of his life. As time progressed, the thickness of the outlines became more pronounced and the shapes increasingly simplified and abstract. In the flat compositions and thick black lines, so typical for Yoors’ oeuvre, one can see the influence of Matisse, but most of all that of the stained glass practice of father Eugene and its dark lead structures that serve both to outline figures as to hold together panes of glass.

Saul Leiter (Pittsburgh, US, 1923 – New York, US, 2013)

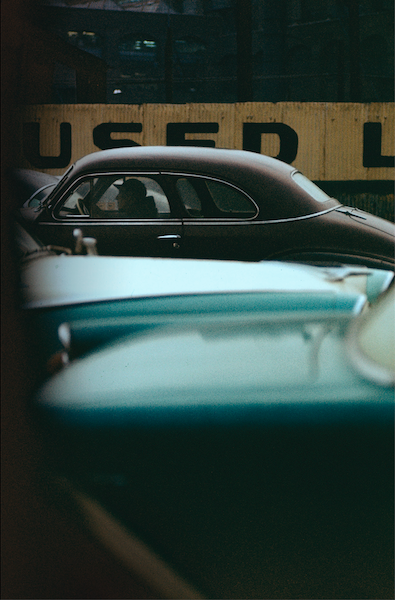

Gallery FIFTY ONE presents a selection of never-before-seen images by Saul Leiter, following the recent book release of ‘The Unseen Saul Leiter’ (Thames & Hudson/Textuel), featuring 76 photographs that were discovered and unveiled during the Saul Leiter Foundation’s excavations of the artist’s color slide archive.

At his death in 2013, Leiter left behind a collection of more than 40,000 color slides, only a fraction of which had seen the light of day. The slides contain decades worth of images captured during his daily strolls near his home in New York’s East Village, on vacation with his friends, and traveling abroad on fashion assignments during his 20-year career as a fashion photographer. These pictures on 35mm positive color slide film were mounted in paper, plastic or metal frames and kept by Leiter in his apartment and studio, often organized in boxes labeled by theme.

Leiter regularly projected his slides onto the walls of his apartment to show them to friends (not having the funds to print them), and sometimes carried a selection to art directors of fashion magazines, presenting them on light boxes. He put a selection of his color slides in shadow boxes to stand next to his paintings for a solo exhibition at New York’s legendary Tanager Gallery in 1955-56, and his slide work was also included in a 1957 talk by Edward Steichen at the MoMA, titled ‘Experimental Photography in Color’. However, only a small percentage of these images were printed during Leiter’s lifetime, with many of them appearing in his first monograph ‘Early Color’ (Steidl) published in 2006, when the artist was already in his eighties. The vast remainder of his color slide archive remained locked away for decades, invisible to anyone. “The world has seen only the tip of the iceberg,” Leiter would say.

In 2018, the Saul Leiter Foundation, under the direction of Margit Erb, began excavating this buried treasure, in collaboration with German scholar Elena Skarke. They started to archive, identify and date (where possible) this vast body of work, with an initial focus on Leiter’s non-commercial slides from 1948 to 1970, an undertaking that continues today. The project offers a new perspective on Leiter’s work, revealing before-and-after shots surrounding well-known images, filling in biographical information about his life and art, and showing the advent of new motifs, settings and experiments in his photography. The first presentation of this research was revealed during the 2020 exhibition ‘Forever Saul Leiter’ at the Bunkamura Museum of Art in Tokyo, Japan, as well as in the catalog accompanying the show. Now, out of a total of 10,000 color slides initially considered, the freshly released publication ‘The Unseen Saul Leiter’ presents a total of 76 new images, of which for the first time also posthumous prints were made. As Margit Erb states in the introduction to the book, “As the gatekeepers of the Leiter archive it was our duty, as well as our privilege, to make our discoveries public.”

The selection was made by Erb herself, who was good friends with Leiter, worked as his assistant during the last twenty years of his life and was appointed by him as the steward of his archive. The two of them closely collaborated on publications and projects about Leiter’s work. In 2013, the last year of his life, Erb assisted Leiter to make a selection of never-before-seen images from his slide archive for the exhibition and publication ‘Here’s More, Why Not’ at Gallery FIFTY ONE. During the creation of ‘The Unseen Saul Leiter’, Erb followed her sense of Leiter’s directives, his distinctive style and his tendency to experiment, all of which she experienced while watching him edit and select his work. The prints were made in the same size (11 x 14 inches) and by the same printer (Philippe Laumont of Laumont Editions) as Leiter’s lifetime prints. During printing, Leiter’s philosophy and guidelines were closely followed, using minimal editing to closely match the color aesthetic of the original film. (Source: The Unseen Saul Leiter, with texts by Margit Erb and Michael Parillo, Thames & Hudson/Textuel.)

A selection of these new images can be discovered on the ground floor of the exhibition, along with a few of Leiter’s small-scale abstract gouache paintings.

Louis Stettner (New York, US, 1922 – Saint-0uen, France, 2016)

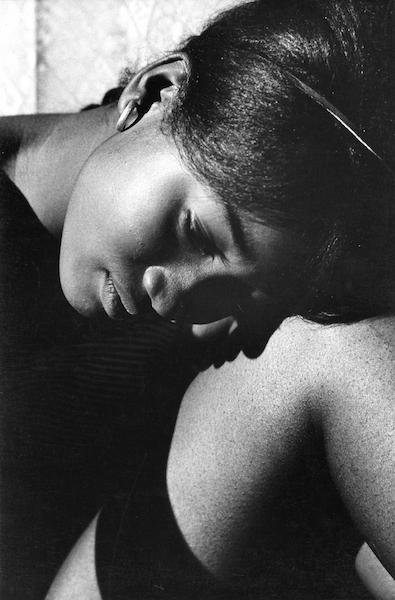

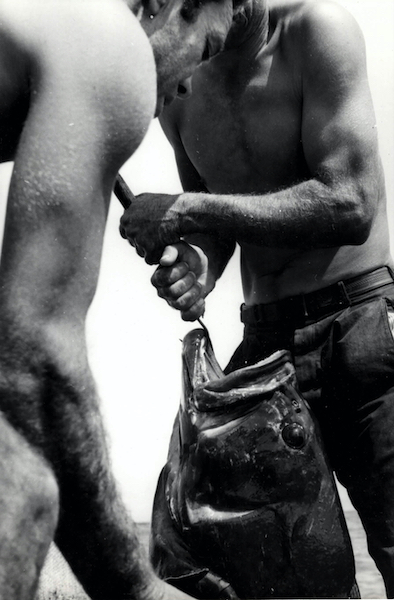

Central to this exhibition is a selection of vintage prints from Louis Stettner’s series ‘Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen’, a photographic account of the artist’s several day trips aboard a small fishing boat in Ibiza in 1956. Stettner made a book layout about his experiences in which images were alternated with texts (reports of dialogues between the two fishermen Pepe and Tony, historical and technical information about fishing and life on the island, etc.). Never published, the maquette disappeared among his photographic archives only to be rediscovered during preparatory research for the retrospective exhibition ‘Ici Ailleurs’ (2016) at Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, and where the original maquette is also now preserved.

In ‘Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen’, Stettner portrays the two men and their occupation with great dignity and grace. Close-ups of the fishermen’s faces, gazes, hands, elegant gestures and tense muscles are interspersed with wide shots of the surroundings and of the boat itself. This renders the whole very cinematographic; the viewer is carried away on the rhythmic movements of the sea and witnesses the action (but also moments of rest), on board from the front row. The series is illustrative of Stettner’s fascination and admiration for the daily lives of the working class, a subject he himself described as a ‘lifetime commitment’. However, the texts he wrote to accompany the images of ‘Pepe and Tony’ are not merely a heroic homage to the fisherman in action, but also testify to concerns about the survival of the occupation against the background of the upcoming industrialization of the fishing industry. From Stettner’s point of view, these men not only fight a brave, daily battle against the sea, but also against the inevitable progress of the time, post-war capitalism and the rise of mass tourism.

This attention on economic and social issues is typical of Stettner’s humanist beliefs and intense social commitment. He was strongly influenced by the Photo League (1936-51), a leftist, even communist-oriented cooperative of New York photographers striving for social activism through photography. Stettner would pursue this philosophy throughout his life, always placing the human element at the center of his photography: “ [I] have never been interested in photographs based solely on aesthetics, divorced from reality.” In his monthly column ‘Speaking Out’ (published in the magazine, Camera 35, from 1971 to 79 and later renamed ‘A Humanist View’), in which he analyzed the history of photography, he showed himself a fierce critic of the new generation of photographers, calling their work “photographic ego-tripping more aptly described as ‘belly button’ photography… photographs characterized by pretentiousness and an artificial stiffness that often asks us to take seriously works having the casualness, lack of significant structure and content of a snapshot.”

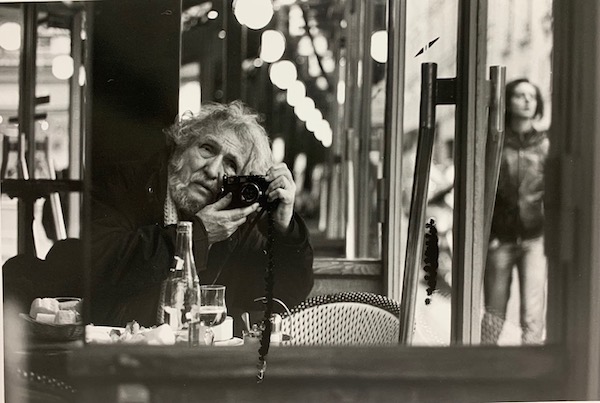

On the other hand, Stettner defined himself as a realist; he focused on quotidian subjects and wanted to portray life as it presented itself to him in a natural, non-manipulated way. However, his images were seldom merely ‘objective‘ representations of reality as demonstrated, for example, by the New York School of the 1940s, whose straightforward imagery sought to highlight the harsh living conditions of the poor. With his often complex compositions and play with shadows, reflections and obstructions such as weather elements, Stettner, introduced a subjective plan that separated the viewer from the subject. His oeuvre can therefore rather be described as ‘subjective realism’; an interesting position that may have stemmed from his influences from both the US and France.

After serving as a combat photographer in the Pacific during World War II, Stettner went to study in Paris, where he became an active and valued member of the local post-war photography scene. In 1952 he returned to the US, but settled definitely again in Saint-Ouen, near Paris, in 1990, where he would photograph, paint and sculpt until the end of his life. Through his introduction to the French Humanist School, whose vision seemed to echo that of the Photo League, Stettner developed a unique photographic language that blended the boldness and directness of American street photography with the more sensitive humanism more characteristic of his Paris contemporaries.

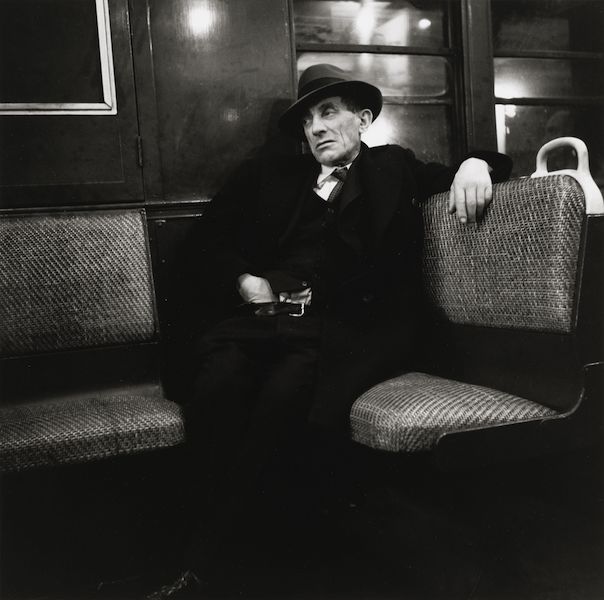

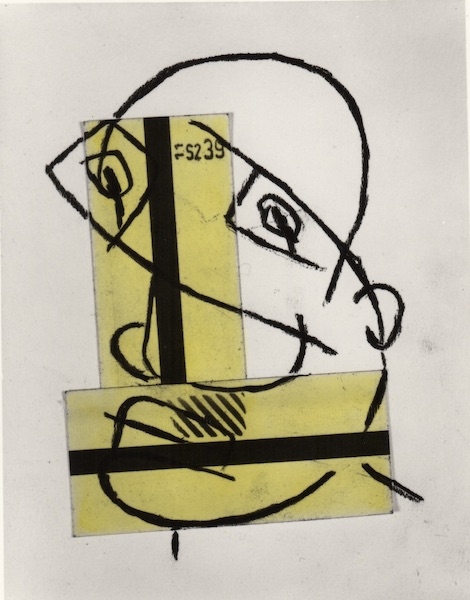

The remainder of the exhibition shows examples of these various influences and therefore, diverse oeuvre such as two images from a 1946 series in which Stettner photographed people on the New York subway returning from their work, their bodies often surrendering to fatigue. Or images of Nancy, a young Beatnik girl the photographer followed for a 1959 photo reportage for Pageant Magazine. Finally, the exhibition includes the 1991 series ‘Héros du Métro’, consisting of black and white photographs of Stettner’s drawings on collages of metro tickets, which he then hand colored with a yellow dye. These works are part of a larger series called ‘Marché aux Puces’, in which Stettner started to paint, draw and make assemblages with found objects and his own photographs after inspiring visits to a Parisian flea market as well as his introduction to Art Brut and its original form of expression, out of the mainstream of traditional art. It is one of the few examples in which Stettner abandoned the realism that was usually so present in his work.

A retrospective exhibition on the life and work of Louis Stettner is currently being prepared by the Fundacion MAPFRE in Madrid, Spain, and will take place in 2023.