Diary of a Dancer

Elinor Carucci

02/12/2005

21/01/2006

Gallery FIFTY ONE

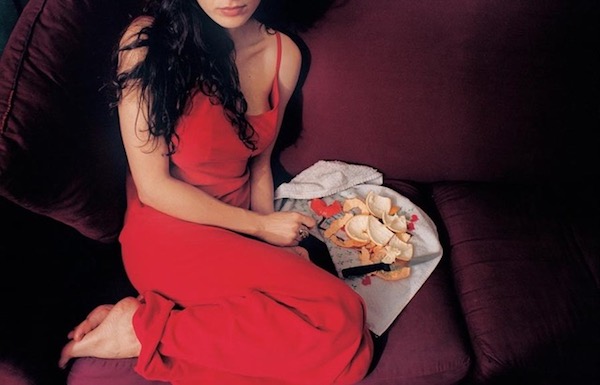

Fifty One Fine Art Photography is proud to present the new work by Elinor Carucci. Carucci’s latest project is called Diary of a Dancer. The complete series is also collected in a gorgeous SteidlMACK edition.

This collection of photographs chronicles the Israeli artist’s alter ego as a Middle Eastern or belly dancer and was made during a three-year period in which she mostly performed in New York City. As she was always on the move and had no time to ponder on things these photographs are a series of fleeting glimpses and reflect the way she actually experienced this journey.

Middle Eastern dance is not just choreographically complicated; it is also direct, sexual, warm, alive. More than that it is, in it’s own way, truly intimate. It could not be all this if it were not performed in ordinary settings; among rather than in front of, audiences. That is why she started to photograph the people for whom she performed in different communities, the other dancers and herself, before and after the show. As she herself is in the spotlight she observes her audience but in the mean time is observed by them. The photographs reflect this interaction between the public and herself.

In addition to photographing in her recognizable style, she has shot much of this work in an unexpected panoramic format. She continues to keep a very personal approach photographing herself and other dancers in performance and at the various venues with different audiences. In contrast to her earlier work on her family where the camera was informed she, here, had limited opportunities to study what she might photograph.

Much of her new work has been constituted out of fascination and curiosity. The occasions on which she performed, were usually happy events, and as Carucci says: “… it is surprisingly simple how in a thirty minute glimpse, emotions are contagious. You actually feel the sheer joys of other people; sometimes even recognize their hidden pains and bitterness. It is not so much the content of the emotions but the facility of sharing them, however briefly, that endlessly fascinated me. More than that it helped me sustain an optimism which I can’t exactly put in words, but which, I hope, I managed to catch, however fleetingly, on film.”

Elinor Carucci has become one or the best-known young photographers working today. She has been published regularly in most major publications, ranging from New York to The New York Times Magazine, W, Details, and so on. She has exhibited internationally and gained respect as a teacher and lecturer.

Her many honors include the prestigious International Center of Photography Infinity Award for Young Photographer and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Chronicle Books published her book Closer in 2002. Carucci’s photographs are included in the Museum of Modern Art among other collections.

Elinor Carucci

As Elinor Carucci’s photographic diary continues to evolve, she takes us into the details of her surroundings, her family life and her home. By narrowing the way she looks at things, the more she is able to see. Carucci takes the viewer into a very private part of her world. Marks on a body from bed sheets after waking, the imprint of a zipper on skin looks familiar and beautiful, a few dark hairs on an upper lip reveal a flaw in an otherwise perfect and sensual mouth. Carucci photographs the stitches on a finger, and it becomes eerie and striking, mimicking the pattern of eyelashes from a very separate and quiet photo. All are the results of reality, living and seeing, capturing accidents with artful intention.

Since her gallery debut in 1997, Carucci’s reputation has grown internationally with solo exhibitions in London, Frankfurt, Prague, and Jerusalem. Her work has been extensively published and collected by numerous institutions and private collectors.

biography

Born in Jerusalem, Israel in 1971

Lives and works in New York, US

Background

At first, Carucci photographed her mother, father and brother, and then later the extended family. At a certain stage, she began shooting her mother and herself as a series of pictures, serving as work subjects.

The second stage of her work was shooting in colour. No advance warning, no cooperation. To snap, to develop, to check and over again. The frame became flexible and hospitable. What she had previously considered improvisation, marginal, came close to the centre and became the theme itself.

But how much can one interfere in the pictured situation? Does altering the lighting create a different situation? Does a bit of cleaning up or changing clothes before photographing keep one faithful to the reality of what one is trying to document? Maybe some of the photos are what you would like things to be and not how they really are?

The preferred situation: Don’t think, just shoot, just shoot.